Innovation is not just about technology.

Or engineering.

Anyone in the tech biz, given 5 minutes, can come up with half a dozen examples of “cool,” superbly engineered products that were commercial failures. Just to make the point, here are a few:

- Xerox’s GUI interface (stolen by Apple, and then stolen from Apple by Microsoft, before it became a commercial success).

- Sony’s Beta video tape format.

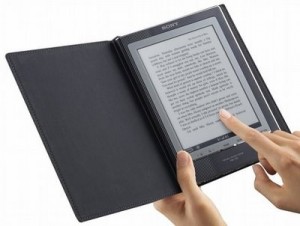

- Sony’s Librie ebook reader.

- Netscape web browser.

- Apple’s eWorld.

- Second Life.

- Eight-track cassette players.

- Rotary engines.

These were all interesting technology implementations. Most of them were ground breaking innovations and most of them were superbly executed from an engineering point of view. But they were also commercial flops.

Brain power and imagination are not the problem when it comes to “cool” products that fail. The engineers that I have met over the years, engineers working on products as diverse as DNA sequencers and eCard web sites, have been very bright people.

So why do some innovative products become game changers while others crumble in the face of less innovative existing competition? To answer this question, we must first answer the question: What is a product?

A product is an object or a service provided by a business to a customer to solve a problem, a want, or a need at a price that the customer is willing to pay.

Simply put, successful products, especially products based fundamentally on technological innovation, are made up of a well balanced mix of:

- features and function

- price point

- quality

- perception – brand

- delivery or distribution, including advertising and promotion

- after sale service and support

Whether the innovative new product creates a new product category, disrupts an existing product category, or simply provides the manufacturer with a competitive advantage, all of the key elements of what makes a product must come together to make the product a commercial success.

Sony, for example, made the same mistake twice. Famously, in the war over which video tape format would rule the consumer market, Betamax or VHS, Sony had arguably the better engineered product: betamax tapes and machines were smaller and the image quality they produced was better. But Beta was also more expensive and, most importantly, Sony failed to convince content providers to make their movies available on the Beta format. Consumers didn’t care whether or not the Beta format was better; they only cared which format had their favorite movies and TV shows.

That was in the 1970’s. In 2004, Sony made the same mistake with the Librie, its pioneering ebook reader. Sony had first mover advantage in a long anticipated product category, but Sony focused on the technology side of the product, especially the e-ink component, which was very cool and new at the time. Unfortunately, Sony failed, once again, to provide content. Consumers just won’t buy an eReader if little content is available or the material is not easily accessed or, worse, the material that is available is not the material consumers want to read, and the Librie suffered from all three of these content problems.

When an established and experienced consumer products company, such as P&G or Unilever, rolls out a new product, they carefully plan the entire package, including price, distribution, branding, and customer support. Early stage tech companies often don’t feel they have the time and resources for such luxuries as market research and distribution planning, so they simply focus on the technology behind the product. Technology is what the founders are familiar with and it provides the IP that the investors feel they are paying for. The result is a higher than necessary failure rate.

Innovative technologies still need to be delivered as part of a complete product package, which means all the other pieces of what makes a product need to be taken as seriously as the technology that makes the product possible.