One useful way of analyzing the concept and processes of innovation is to make a distinction between Revolutionary and Evolutionary Innovation. Both are valid and both produce excellent results. But each is better suited to a different environment and, unfortunately, it’s not clear which produces better results.

Revolutionary Innovation

Revolutionary Innovation seeks to adapt the world to new ideas.

Revolutionary innovation is the type we see and hear about most in United Statese. On the one hand, it can quickly make available wondrous new products and services. On the other, it is disruptive and expensive, and it produces unpredictable outcomes. Revolutionary Innovation requires large pools of highly risk-tolerant investors who are prepared to make large capital investments to try something completely new, and those investors require, in turn, very large returns for the few major successes that they come across.

Diversity and high levels of education are essential ingredients of revolutionary innovation. Entrepreneurs and investors are much more likely to develop wholly new approaches to business and technology if their day-to-day experiences include exposure to and stimulation by a host of differences in thinking and working, and if they have both the training and the intellectual capacity to act on new ideas.

Unsurprisingly, heroic role-models and celebration of the individual are conducive to revolutionary innovation. A social system that admires game-changers like Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Jeff Bezos is likely to produce a large number of aspirants trying to achieve the same glory.

Digital photography is an excellent example of revolutionary innovation. It changed the way people take, share, and use pictures, destroying an entire ecosystem of companies from local camera stores to giant manufacturing companies like Kodak. It also made possible whole new business models: Facebook would not exist on the scale it does today without digital photography.

Evolutionary Innovation

Evolutionary Innovation seeks to adapt new ideas to the existing world.

Evolutionary innovation dominates in countries like Japan, but it is also broadly followed in most very large corporations, regardless of their national heritage. Evolutionary innovation tends to be incremental in nature and less expensive to develop than revolutionary innovation. Evolutionary innovation focuses on preserving or gradually changing existing fundamentals, including people, product, and business relationships. Because the changes tend to be smaller, investment in evolutionary innovation tends to be smaller, and because the destruction wrought by evolutionary innovation tends to be less dramatic and spread over a longer time frame, the costs, both in terms of dollars and in terms social and business disruption, tend to be smaller as well.

In part because the consequences of failure are smaller, evolutionary innovation also dispenses with risk takers and the need for big rewards, diversity in thinking and practice, and lionized role models.

The automobile companies of Japan, especially Toyota, exemplify evolutionary innovation. Through a steady stream of small changes in manufacturing, design, distribution, support, and integrated technologies, Japanese auto makers quietly achieved the goal that all Silicon Valley and Silicon Alley entrepreneurs say they aspire to but rarely reach: World Domination.

Revolutionary vs Evolutionary: Which is Better?

There’s no easy answer to which is better, revolutionary innovation or evolutionary innovation. Evolutionary innovation is clearly more boring, but it’s also more secure because it’s more predictable and manageable.

Companies and economies that rely on evolutionary innovation need to keep that innovation coming at a rapid rate or they will get left behind by someone else’s innovations. Similarly, no matter how quickly they may innovate in many small ways, evolutionary innovators are subject to game changers from the revolutionary innovators. As mentioned earlier, evolution is less expensive, both on the development side and on the consequences side, but entrenched interests, which tend to emerge when evolutionary innovation dominates, can stifle changes and improvements that are desired by and in the best interest of the majority in favor of smaller or entirely different changes and improvements that are in their own best interests.

In the long run, businesses and economies probably benefit from having a combination of both forms of innovation, which means having the social and economic infrastructure to support both.

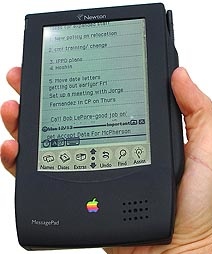

Compare Apple’s Newton with its iPhone successor. Take a look at the pictures of the two devices with the hands normalized to (roughly) the same size. Consider the dimensions of the two instruments. Now look at the screen layout. Look at the styling of the cases. Think about the way users are expected to interface with the devices (stylus vs fingers). Consider the range of uses (apps) available for each and the ease with which users can add or remove functionality (and the ways that Apple makes money from the apps).

Compare Apple’s Newton with its iPhone successor. Take a look at the pictures of the two devices with the hands normalized to (roughly) the same size. Consider the dimensions of the two instruments. Now look at the screen layout. Look at the styling of the cases. Think about the way users are expected to interface with the devices (stylus vs fingers). Consider the range of uses (apps) available for each and the ease with which users can add or remove functionality (and the ways that Apple makes money from the apps).