Librarians frequently use the terms outreach, marketing and engagement interchangeably. Many people, not just librarians, do. However, the terms are fundamentally different, and the underlying philosophy of how a library works and participates in its community affects which term applies. It is essential for librarians, especially library leadership, to understand the differences.

Outreach: The primary – almost exclusive – function of outreach is to increase awareness within an audience. Libraries conduct outreach to make community members aware of their services and programs. The underlying objective of outreach is to increase attendance or use of existing services and programs developed by the library for the audience. Usually this is accomplished  through unidirectional communications such as posters in the library, e- newsletters, social media posts, handouts available through the circulation or reference desks and blurbs or articles in local news outlets. Outreach is fundamentally a PR function. It consists of outbound, unidirectional communication from the library to thecommunity.

through unidirectional communications such as posters in the library, e- newsletters, social media posts, handouts available through the circulation or reference desks and blurbs or articles in local news outlets. Outreach is fundamentally a PR function. It consists of outbound, unidirectional communication from the library to thecommunity.

Marketing: The function of marketing is rarely used by libraries. Marketing has three essential parts. First, marketing is a proactive effort to identify distinct audiences within a community. These audience might be defined, for example, by age, language, education level, gender identity, political views, reading habits or any combination of characteristics. Next, marketing requires the institution to make a proactive effort to understand the wants and needs of each group it serves and what motivates the people who make up that group. Young adults uncertain about their gender identities have information interests and reading / browsing habits that are different from the information interests and reading / browsing habits of retirees with grandchildren and health problems.

Marketing also assumes that there are segments of the community that the library does not reach well, and, because they are part of the community, we should connect with them. Marketing then assumes that we may not know the people in these groups as well as we think, and we need to understand them to provide them with the programs and services they want. Therefore, we librarians need to identify the various groups in our communities, and then we need to understand them.

Second, marketing uses what it has learned about the various segments of its community to change existing programs or develop new ones that meet the needs and interests of those segments.

The last, and not least, component of marketing is much like outreach. Marketing includes letting the community  know about all these great programs and services that the library has developed for it based on what the library has learned about the various segments of the community.

know about all these great programs and services that the library has developed for it based on what the library has learned about the various segments of the community.

Marketing is a continuous cycle of learning about the community, how it is changing and what new segments are emerging, and then adjusting the library’s mix of programs and services to meet the community’s current needs and interests. Outreach is just a piece of marketing.

Engagement: Both outreach and marketing start with predetermined assumptions about the role of the library in the community and those assumptions are made by the library. Engagement allows the community to have a bigger say in the role of the library in the community.

Engagement, like marketing, starts with identifying the constituencies within a community and then goes to them and asks them about their aspirations for their community. The community, not the library, is the center of the discussion. Instead of asking what the community wants from the library, which is the classic marketing question, the basic engagement question is what does the community want for itself. The library then has to figure out how to facilitate those aspirations.

Sometimes the best way to facilitate a community  aspiration will require the library to develop programs and services within the library with input from the community, but many times the best way for the library to facilitate a community aspiration will be to empower individuals or other organizations within the community to work towards related goals. Richard Harwood of the Harwood Institute refers to this as “turning outward”. Instead of the library looking at itself as an institution first, the library looks first and primarily at the community for a definition of what the library is and does.

aspiration will require the library to develop programs and services within the library with input from the community, but many times the best way for the library to facilitate a community aspiration will be to empower individuals or other organizations within the community to work towards related goals. Richard Harwood of the Harwood Institute refers to this as “turning outward”. Instead of the library looking at itself as an institution first, the library looks first and primarily at the community for a definition of what the library is and does.

The ALA has developed a program called Libraries Transforming Communities (LTC). LTC is an engagement program for libraries and includes tools and training for library staff. LTC (engagement) makes it possible for libraries to work with their communities to develop programs and services in conjunction with the community to achieve aspirations defined by the communities.

Libraries that engage with their communities not only provide programs and services defined and created by their communities, they also facilitate work done by others.

“Bad libraries build collections, good libraries build services,

great libraries build communities.“

R. David Lankes

Outreach, therefore, is fundamentally the PR function of marketing. Marketing is fundamentally the cyclical process of learning about a library’s community, building and revising library programs and services to meet the needs of the community and then using outreach to make the public aware of those programs and services. Engagement, however, puts the community front and center and calls on the library not only to build library programs and services but also to enable and participate in programs and services developed by the community itself or by other institutions. Engagement makes the library a member of the community.

through unidirectional communications such as posters in the library, e- newsletters, social media posts, handouts available through the circulation or reference desks and blurbs or articles in local news outlets.

through unidirectional communications such as posters in the library, e- newsletters, social media posts, handouts available through the circulation or reference desks and blurbs or articles in local news outlets. know about all these great programs and services that the library has developed for it based on what the library has learned about the various segments of the community.

know about all these great programs and services that the library has developed for it based on what the library has learned about the various segments of the community. aspiration will require the library to develop programs and services within the library with input from the community, but many times the best way for the library to facilitate a community aspiration will be to empower individuals or other organizations within the community to work towards related goals. Richard Harwood of the Harwood Institute refers to this as “turning outward”. Instead of the library looking at itself as an institution first, the library looks first and primarily at the community for a definition of what the library is and does.

aspiration will require the library to develop programs and services within the library with input from the community, but many times the best way for the library to facilitate a community aspiration will be to empower individuals or other organizations within the community to work towards related goals. Richard Harwood of the Harwood Institute refers to this as “turning outward”. Instead of the library looking at itself as an institution first, the library looks first and primarily at the community for a definition of what the library is and does. If a library serves a community of 50,000 residents, maybe 1,000 (2%) of them follow the library on FB. Worse (and many libraries don’t realize this) few FB posts reach even half of the people who follow the library. In fact, in most cases a library is lucky if any given post reaches 20% of its FB followers.

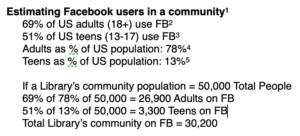

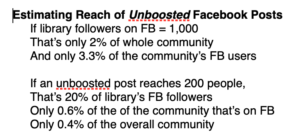

If a library serves a community of 50,000 residents, maybe 1,000 (2%) of them follow the library on FB. Worse (and many libraries don’t realize this) few FB posts reach even half of the people who follow the library. In fact, in most cases a library is lucky if any given post reaches 20% of its FB followers. Given that math, in a community of 50,000 people, only 200 (0.4%) residents will see any given post. If a library announces a big event, such as an interactive webinar on keeping kids engaged with school during the pandemic, the library will reach only a tiny percentage of the community with its announcement. Furthermore, many of those who are reached may not be parents of elementary school age kids. If a third of the people reached by the post are too young or too old to have children, out of 50,000 residents only about 80 people who might possibly be interested will see the announcement.

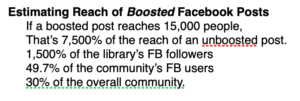

Given that math, in a community of 50,000 people, only 200 (0.4%) residents will see any given post. If a library announces a big event, such as an interactive webinar on keeping kids engaged with school during the pandemic, the library will reach only a tiny percentage of the community with its announcement. Furthermore, many of those who are reached may not be parents of elementary school age kids. If a third of the people reached by the post are too young or too old to have children, out of 50,000 residents only about 80 people who might possibly be interested will see the announcement. For $10 per day over a five day period, NCC Japan boosted a post to reach more than 17,000 Facebook users who were selected based on geography, education, profession and academic interest. None of the 17,000 who saw the boosted NCC FB post were current followers of NCC. Over 700 people engaged with the post, clicking through to NCC Japan’s FB page, and many became NCC FB followers. Even those who did not engage with the ad at least had NCC’s name and logo presented to them, which will make them more receptive to future NCC boosted posts.

For $10 per day over a five day period, NCC Japan boosted a post to reach more than 17,000 Facebook users who were selected based on geography, education, profession and academic interest. None of the 17,000 who saw the boosted NCC FB post were current followers of NCC. Over 700 people engaged with the post, clicking through to NCC Japan’s FB page, and many became NCC FB followers. Even those who did not engage with the ad at least had NCC’s name and logo presented to them, which will make them more receptive to future NCC boosted posts.